身為長(zhǎng)者,起初我并不知道該傳遞什么樣的智慧或榜樣給后人——我所青睞的英雄蝙蝠俠不夠嚴(yán)肅,福爾摩斯自稱(chēng)是個(gè)癮君子,而郝思嘉說(shuō)的“明天又是新的一天”又未免太陳詞濫調(diào)。然而,通過(guò)伊努伊特人富于智慧和內(nèi)涵的族長(zhǎng)以及古代日本三代共建寺廟的事例,我明白了,其實(shí)真正的人生智慧就蘊(yùn)藏在我們幾十年的歷練中。

By Margaret Atwood[1]

伍艾 選注

Earlier this year I participated in an unusual video series called Wisdom Keepers. It’s planned as a number of short interviews with older people of accomplishment, from dancers to environmentalists to writers such as me, and is intended as a motivational tool for an audience of teenagers (now known as “young adults”).

Over the years, we adults have found ourselves dividing into subgroups: the young adults; the less-young adults; the moment of despair when we turn 30 and believe we’ve kissed our youth farewell; the thirty-somethings, worried about their first mini-wrinkle; the middle-aged in denial; those who are what the French call “a certain age”; and the truly mellow, sagacious, and mature.[2]

The last category is the part where you’re supposed to have acquired some wisdom. It’s also the part where you keep wondering when the stuff[3] is finally going to turn up, because you don’t feel any wiser than you did at age 20. If anything, less wise: At 20 you know everything; at 70 you’re not so sure. And if you don’t know where you’ve put the wisdom, how can you be expected to be a keeper of it? That was my first reaction on being asked to be a Wisdom Keeper.

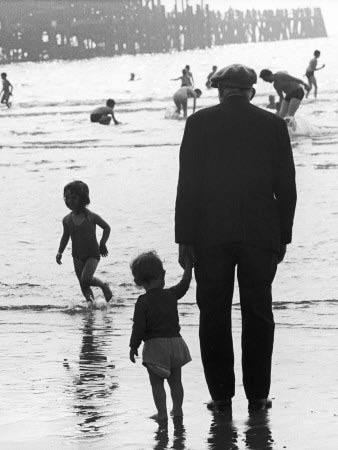

I have felt a little wise on occasion. “Grandmother, how did you get to be so very old?” my five-year-old grandson asked me.

I lowered my voice as if imparting[4] a valuable secret. “Through not dying,” I said. “That’s the trick!”

“Oh,” he said wonderingly[5].

It’s not such bad advice. Nonetheless, the thought of being featured in Wisdom Keepers made me panic.[6] “When you were young, who was your favorite hero in real life or in history?” the questions began. It would be poor role-model behavior for me to say, truthfully, “Long John Silver, the ruthless and bloodthirsty pirate in Treasure Island.”[7] I considered Batman, but a man—however virtuous and musclebound—who’d climb into a skintight bat costume and then into a Batmobile in order to do his good deeds lacked a certain seriousness.[8] “Sherlock Holmes” would have been an honest answer—but he was an avowed cocaine user, and might be looked at askance by the high-school boards of today.[9]

And as a woman, wouldn’t I be expected to produce an admirable female? Who would do? There were a lot of woman writers I could have proposed—Emily Bronte, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Barrett Browning—but why wish a scribbler’s fate upon the young?[10] I ducked[11] the question by saying, not inaccurately, that I wasn’t much good at heroes.

The other questions for Wisdom Keepers were equally perilous[12]. “What do you mean by leadership?” provided an opportunity for snide jokes about politicians, but (believing as I do that everyone should vote) I didn’t want to encourage cynicism.[13] To “What motto or belief guides you through the tough times?,” Gone With the Wind’s “Tomorrow is another day” seemed barely sufficient.[14] “If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans,” though succinct[15], is not a thing the young need to be told: they’ll discover it all too soon.

You may ask, as I asked myself, “Why not say no? There’s no law that says you have to be a Wisdom Keeper. Why not declare yourself a Stupidity Keeper instead, and opt out[16]?”

The answer has to do partly with the man behind the idea. Wisdom Keepers is the project of Dr. Joe MacInnis, the physician-turned-pioneer of deep-sea-diving techniques in the Arctic.[17] Dr. Joe has led more than 30 expeditions, developed many new techniques for use in extreme conditions, and explored many a sunken wreck, including the Titanic.[18] For dealing with life-threatening conditions he stresses such characteristics as resilience[19], courage, a sense of humor, and the ability to think as a member of a team. He also happens to be a very nice person, and, as you get older, it’s often to the person rather than to the project that you find yourself not saying no. Your grandfather was right: character does matter.

One of the things Dr. Joe and I have in common is a love of the Arctic. Being in that vast expanse of land and sea above the tree line is like looking at the bones of the world.[20] You know how small you are, how easily snuffed out[21]—and also how important your life-support systems are, other people among them.

I’d traveled in the Arctic a number of times, though not nearly as many as Dr. Joe. I suspect that the roots of his Wisdom Keepers project lie there, with the Inuit—who happen to possess so many of the qualities Dr. Joe prizes among those who live and work at the extreme edges of human experience.[22] He must have observed the respect they pay to Elders, and he may also have wondered why our society, with its emphasis on youth, has been losing its intergenerational connections.[23] Wisdom Keepers may be his way of bringing into being an Elders tradition among non-Inuit.

While visiting in the Arctic, I had been told a number of things about Inuit Elders. First, you can’t become an Elder just by getting old; it’s a title bestowed[24] by others. You never push your advice, but you offer it if asked. “You can tell who the Elders are,” said my informant[25]. “Just watch a group. The Elders are the ones to whom the others are always bringing cups of tea.” When an Elder speaks, people listen. But Elders don’t speak often.

An Elder knows what to do in times of difficulty. Elders acquired that knowledge by having endured hard times before. As one of our old sayings puts it, “Good judgment comes from experience. Experience comes from bad judgment.”

In earlier societies, especially those living in harsh environments, at a time when the life expectancy was 35,[26] the rare individual living to 60 would have seen many more times of crisis than the younger people. He or she would have had a better idea of how to face those dangers. In traditional Japan it was the custom to tear down and rebuild wooden temples at set intervals.[27] So that the rebuilt temple would exactly resemble its predecessor, three generations of master craftsmen were always employed: the apprentices, who were learning; the master craftsmen of middle years, who had already lived through one temple rebuilding; and the oldest generation, who’d been through the process twice before and could coach the other two.[28] One of the reasons to keep wisdom, it seems, is so you can pass it on when required.

Many people feel we’re living through a crisis now. The young, especially—those who have known only the affluent[29] times of recent years—have been shocked by the global recession. They were fed a number of accepted truths that turned bottom side up overnight:[30] that spending was always a good thing to do, that a house would always increase in value, that the rich and powerful always knew what they were doing. Not so, it seems, nor is the present situation unprecedented[31], but those under 35 have never lived through anything like it.

Perhaps it’s time for our own Elders (our Wisdom Keepers) to share their experience with younger generations who want to know—and also need to know—how to deal with hard times:

“This is how you stretch a dollar and serve a leftover,”[32] they might say.

Or, “The important things in life aren’t things.”

Or, “Keep your nerve[33]. Don’t panic. The only way out is through.”

Or, “Hanging your clothes to dry doesn’t cost a cent.”

Or, “ ‘We’ is a more powerful word than ‘I.’”

Or, “The human race has been through the bottleneck[34] before.”

Or even a simple, “We can do this.”

You’ve got your own list? Time to share it—though, like a true Elder, only when asked.

Vocabulary

1. Margaret Atwood:瑪格麗特?阿特伍德,當(dāng)代加拿大知名作家、詩(shī)人。

2. farewell: 告別;the thirty-somethings: 三十來(lái)歲的人;mini-wrinkle: 小皺紋;in denial: 持否定態(tài)度的;mellow: 成熟的,穩(wěn)健的;sagacious: 有洞察力的,有智慧的。

3. stuff: 東西,此處指“智慧”。

4. impart: 告知,透露。

5. wonderingly: 覺(jué)得奇怪地。

6. feature: 作為主要角色,主演;panic: 驚慌失措。

7. role-model: 行為榜樣;Long John Silver: 海盜小說(shuō)《金銀島》(Treasure Island)中聲名狼藉的獨(dú)腳大盜;ruthless: 冷酷無(wú)情的;bloodthirsty: 嗜殺成性的;pirate: 海盜。

8. 我想過(guò)蝙蝠俠,但一個(gè)穿上緊身蝙蝠俠衫、開(kāi)著蝙蝠俠戰(zhàn)車(chē)去行俠仗義的人——無(wú)論他品德多么高尚、肌肉多么發(fā)達(dá)——都缺乏某種嚴(yán)肅性。Batman: 蝙蝠俠,美國(guó)卡通、電視和電影人物,白天是百萬(wàn)富翁、社會(huì)名流Bruce Wayne,夜晚則扮成身著披風(fēng)頭戴面具的俠士,在紐約市打擊罪犯。

9. Sherlock Holmes: 福爾摩斯,英國(guó)作家柯南?道爾(Conan Doyle)所著一系列偵探小說(shuō)中的主人公,一位推理能力極強(qiáng)的大偵探;avowed: 自認(rèn)的,公開(kāi)宣布的;askance: 懷疑地,不以為然地;board: 委員會(huì),董事會(huì)。

10. propose: 建議;Emily Bronte, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Barrett Browning: 勃朗特(1818—1848)和奧斯汀(1775—1817)是兩位英國(guó)女小說(shuō)家,代表作分別為《簡(jiǎn)?愛(ài)》和《傲慢與偏見(jiàn)》,勃朗寧(1806—1861)為英國(guó)女詩(shī)人,代表作《孩子們的哭聲》;scribbler: 作家。

11. duck: 回避。

12. perilous: 危險(xiǎn)的,這里指“不好回答的”。

13. snide: 諷刺的,挖苦的;cynicism: 嘲笑挖苦。

14. motto: 格言,座右銘;Gone With the Wind: 小說(shuō)《飄》,后改編為電影,譯作《亂世佳人》。

15. succinct: 簡(jiǎn)明的。

16. opt out: 退出。

17. physician-turned-pioneer: 醫(yī)生出身的先驅(qū);deep-sea-diving: 深海潛水;the Arctic: 北極。

18. expedition: 遠(yuǎn)征,探險(xiǎn);sunken: 沉入水底的;wreck: 沉船;Titanic: 泰坦尼克號(hào)。

19. resilience:(活力、精神等的)恢復(fù)力,適應(yīng)力。

20. 身處林木線(xiàn)上方廣袤的陸地和寬廣的海洋當(dāng)中,就好像在注視著世界的脊梁。tree line: 林木線(xiàn),指高山上林木生長(zhǎng)的上限。

21. snuff out: <俚> 斷氣,死去。

22. Inuit: 伊努伊特人,美洲的愛(ài)斯基摩人,常年生活在惡劣的極地環(huán)境中;prize: 珍視。

23. Elder:(部落等群體中的)頭人,族長(zhǎng);intergenerational: 兩代之間的。

24. bestow: 贈(zèng)給,授予。

25. informant: 提供消息的人。

26. harsh: 嚴(yán)酷的;life expectancy: 預(yù)期壽命。

27. tear down: 拆毀;at set intervals: 每隔一段時(shí)間。

28. resemble: 像,類(lèi)似于;predecessor: 前身;master craftsman: 能工巧匠;apprentice: 學(xué)徒;coach: 指導(dǎo)。

29. affluent: 富裕的。

30. 他們被告知的許多普遍真理頃刻遭到顛覆。

31. unprecedented: 前所未有的。

32. stretch a dollar: 指謹(jǐn)慎消費(fèi),不亂花錢(qián);serve a leftover: 利用剩余物(尤指食品)。

33. keep one’s nerve: 保持勇氣。

34. bottleneck: 瓶頸,阻礙。

(來(lái)源:英語(yǔ)學(xué)習(xí)雜志)