|

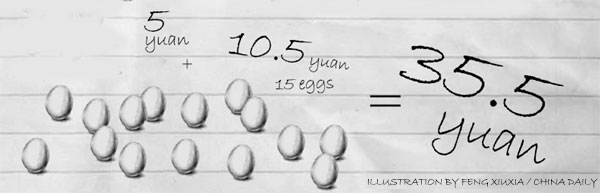

An expatriate in China looks at food from a different perspective, and takes part in a challenge that allows him only $1.50 a day for meals. Justin Ward tells us how and why he did it. As one of the millions of Americans caught up in foodie trend that had hit the nation over the past decade or so, it is hard for me to think of food as anything other than an indulgence. I enjoy cooking and eating so much that I tend to forget that there are 3 billion people in the world who do not view food as a luxury. For them, it means life. Even at the lowest end of the pay grade, expatriates in China make salaries that place them well within the ranks of the country's middle class. Some even get hardship allowance for living here, and the rest probably grumble that they should. Partly in an effort to examine my own privileged status as one of the so-called foreign experts, I decided to take part in the Live Below the Challenge, a global campaign that calls on people to eat on less than $1.50 a day in a show of solidarity with those living in poverty. Launched in May, the campaign was a cause du jour for celebrities, TV chefs and media personalities in the West. The public was treated to tales of anchormen living on off-brand bologna and movie stars giving up their lattes, but the perspective of a developing nation where a large proportion of the world's poor actually live was absent. At various times in history, China faced famine on a mass scale because of invasion, political upheaval, civil war, natural disasters and any other form of calamity imaginable. Now, there are the new problems of rising costs of living and the increasing gap between rich and poor. A fortunate outcome of the lean times is that the experience gave people tools to cope with the challenges. One is the traditional Chinese diet, which I followed rigorously to make it through the five days. Over the week, it became painfully clear why the Chinese words for breakfast, lunch and dinner are translated to "morning rice", "noon rice" and "evening rice", and why the word for "to eat" literally means "to eat rice". Rice became a large part of my own vocabulary and diet as well. I boiled it, fried it with green onions, made it into porridge with a hard-boiled egg for breakfast. And though I never really cared for them before, I learned to love noodles, the other Chinese staple. While most of my counterparts in Western countries were forced to cut out fresh vegetables for the week, I was able to afford some from the low-cost markets within walking distance from my apartment. Of course, calling them "fresh" might be a stretch. I usually found deals by going at the end of the day after the wares had already been picked over by early-rising retirees. My breakfast of rice porridge, and my lunch of noodles with slices of carrot and bean sprouts cost so little that I was left on most days with enough in the budget to afford a couple of cucumbers or tomatoes and eggs. Striving not to waste anything made me realize how much I had been wasting in the past. Everything that was left from a meal I packaged into containers and reused. Yesterday's soup and rice joined forces to become today's porridge. I was able to make it through the week without becoming miserable. Sure, I bemoaned the lack of ice cream and I began to miss the convenience of food that I did not have to cook myself, but in the end, it was not all that bad. In a way, it was enjoyable thinking up creative ways to push the boundaries of the standard of living to which I am accustomed. Poverty has many dimensions, and the cost of food is just one. This week has given me a new take on the value of food. My usual breakfast is at least 3 yuan (49 cents). And I often spend more than my entire food budget for the challenge just for the delivery fee of the food I order in. Before I began, my idea of hardship, as an expat, was lack of access to deli meat and tortillas. While I cannot say I know what it is like to live in poverty now, I think I am one step closer to knowing how little I really know. |

作為一個美國人,我深受過去幾十年來美食主義盛行的影響。對于我來說,食物不是別的,就是享受。我如此享受做飯做菜、吃吃喝喝,以致于有時候我都快忘記了,在這個世界上,不能享受食物的樂趣的人有300萬。于他們,食物僅僅是生存所需。 即使處于薪酬等級末端,在中國的外國人依然可以賺到足夠多錢,使他們過上中產階級的生活。有些人甚至還能得到艱苦生活條件津貼,而那些沒得到的,也許都在嘀咕著為什么自己沒有津貼。 部分為了好好審視一下所謂的“外國專家”身份帶給我的某種特權地位,我最近決定參加一項“最低生存挑戰”活動。這是一項全球性的活動,號召人們每天只花1.5美元(大概9.1元人民幣)在食物上,以表示對過著貧困生活的人們的聲援。 這項活動5月份啟動,一時在西方吸引了很多明星、美食節目的大廚和媒體人士參與。公眾借此享受到很多名人的軼聞趣事,諸如(為了省錢)某主持人吃雜牌紅腸,那些電影明星們放棄了拿鐵咖啡,不過,在中國這樣一個生活著世界上很大比例的貧困人口的發展中國家,卻極少有這類活動。 歷史上,中國常常因為外族入侵、政局動蕩、內戰、自然災害和其他意想不到的災難而發生嚴重饑荒,而現在中國人面臨的問題在于日益增加的生活成本和越來越大的貧富差距。 也許是福禍相依,從困難時期,中國人獲得了應對饑餓挑戰的經驗,中餐就是其中之一。在過去的5天里,我也是嚴格依靠中餐果腹。 過去一周,我從痛苦經驗中明白了,為什么中文里一日三餐被稱作早飯、中飯、晚飯,為什么中文里用“吃飯”這個詞。 “米飯”是我這幾天用的最多的詞,米飯也是我吃的最多的東西。我煮米飯,用蔥炒米飯,還把米做成粥,配著白水煮雞蛋做早餐。 面條是以前我從來不曾留意中國的另一種主食,如今我也變得熱愛面條了。 當西方國家里參加這個挑戰活動的人們不得忍痛舍棄新鮮蔬菜,我卻可以從距離我的公寓幾步路遠的廉價菜市場買回來新鮮蔬菜。當然了,說我買回來的是新鮮蔬菜貌似有點牽強。我通常在晚上去菜市場,這個時候的菜便宜些,但是最新鮮的已經被很早就起床去菜市場的大爺大媽們挑走了。 我早飯就吃大米粥,午飯吃胡蘿卜豆芽面,這些材料非常便宜,大多數日子里,我還能剩點錢買點黃瓜或者西紅柿、雞蛋。 為了避免挨餓,我不敢浪費任何東西,這讓我意識到過去我多么的鋪張浪費。 每一餐吃剩的我都保存起來,留著再吃。昨天剩的湯和米飯第二天鼓搗到一起就成了今天的粥。 經過努力,過去的一周里我活下來了,還過得不太悲慘。當然了,不能吃冰欺凌,我特別哀怨,每天自己做飯,我甚至開始懷念方便食品。不過,說到底,我過得還不錯。 在某種程度上,為了盡可能貼近我平時享受到的生活水準不得不絞盡腦汁,這點我還挺享受的。 貧窮有多面性,食物成本僅是其中之一。 這一個周,我重新認識到了食物的價值。周三的時候,我犒勞自己,吃了一個價值一塊五的包子。平時,我的早餐至少需要三塊錢,而且我常常叫外賣,僅僅外賣服務費就超過這個活動規定的食物預算。 在參加這個活動之前,作為一個外國人,我想象的困頓生活僅僅在于沒有熟肉和玉米餅。現在,我也不能說我完全知道生活在貧困之中是什么樣,但是對于我是多么的無知,我想我比過去知道的多了一點。 (作者:Justin Ward 編譯:劉志華) |