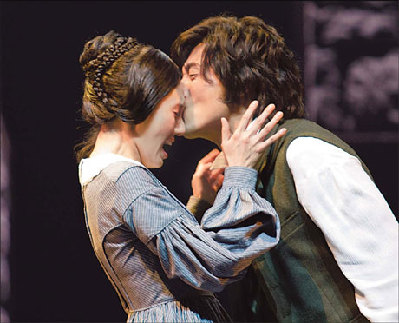

The stage adaptation of literary classic Jane Eyre is one of the latest productions of the National Center for the Performing Arts. [Photo/China Daily]

While movie blockbusters grab our attention the core of the nation's performing arts is live theater.

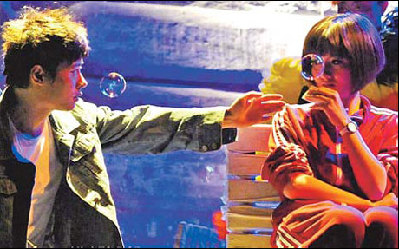

A few hours before the last show of Li Lei and Han Meimei opened, I got a call from Jiang Xiaohan, the female lead. She had fractured her hand and had to wear a glove-like thing that "affected the body language of my character". She would "understand" if I decided to opt out. As a matter of fact, she'd be willing to refund anyone who felt dissatisfied with her hand-impaired performance.

For me, live theater always holds a special fascination exactly because of such unexpected happenings. I go to a show not for perfection, but for a kind of magic only possible when the cast and the audience inhabit the same space and share the same dream.

Judging from the audience response that night - with applause and laughs all the way, nobody was about to take up the offer of a refund.

Li Lei and Han Meimei started its life as a series of high-school textbook illustrations. I did not learn of the inside jokes about the two characters secretly in love because the books were used in the 1990s. That means its target readers were those born in the 1980s, the "it" generation of our era. When they recall these illustrations, they come to realize they have this collective memory.

The play fleshes out what was only hinted at, or more accurately, draws out what fantasies the original readers had about these characters.

Jiang plays Han Meimei, a no-nonsense class president whose biggest headache is the class rebel, Li Lei. It has a neat structure of two timelines running in parallel, one set on the eve of the millennium and the other a decade later, crosscutting into a web of contrast between aspirations and reality.

Jiang is something of a Shirley Temple. She grew up singing and acting on TV. After graduating from Manchester University, she hosted TV shows on CCTV's movie channel. But her versatility comes across in her stage appearances.

In A Midsummer Night's Dream, she played Helena with perfect comic timing, which is a world away from Han Meimei's loneliness, hidden behind a serious facade.

It is the rule more than an exception that performing talents take the stage. You can regularly spot big movie and TV stars give full play to their acting chops in the theater. China's theater scene could be one of the best-kept secrets, with its wide spectrum of offerings and rather limited media exposure.

Li Lei and Han Meimei is just one of a dozen plays I have seen on the subject of the post-80s, and created by the same generation. They invariably tell of the angst and ambitions of youth, but in a language and style uniquely their own.

It may come as a surprise then, that the National Center for the Performing Arts, the nation's 2-year-old national theater, did not dip into contemporary repertory for its latest productions. Instead, it picked Jane Eyre, a literary classic, for stage adaptation.

It is a touch of ingenuity, the relevance of which only becomes apparent when you hear the English governess expound on love and self-respect. Here is a 19th-century personality who forsakes Thornfield Hall when she finds out Mr Rochester already has a wife.

What an antithesis this is to the most talked-about TV drama in China, Dwelling Narrowness, in which attractive women consign themselves to the position of concubines so they can have a place of their own in this age of skyrocketing housing prices.

No wonder the play has clicked with audiences in present-day China.

Jane Eyre has a movie-like fluidity and constant set changes that require modern stage wizardry. On the other hand, Lin Zhaohua, the country's most eminent stage director, advocates the stripping away of all superfluous stage business. He feels that realistic and lavish sets are essentially 19th-century European.

"We don't really have a theatrical tradition, in the academic sense of the word," he said at a recent forum on theatrical art. But it's obvious he wants to create a new tradition - one that fuses the old Chinese style of minimalism, with modern Western abstractness.

Lin, born in 1936, has handled all kinds of productions with equal aplomb, but his penchant for the avant-garde has made him appear to be controversial. He strives to bring the cast closer to the audience, and sometimes the audience complains of not being able to understand what's going on.

Suffice it to say, one goes to a Lin production not for the solace of the familiar but for the challenge of the new. In that sense, he is among the youngest of China's theater directors, as he is constantly reinventing himself.

Stan Lai may have solved the puzzle of experimentation versus popular acceptance. His works are mostly created by his cast, in a creative process rarely seen in mainland theater.

The United States-trained, Taiwan master of theater hit a home run with The Village, which is holding its second mainland tour this year. Spanning 60 years and three families, this panorama of history is the best Chinese-language play I have seen in many decades. It is at once tragic and comic, sweeping and intimate, bold and populist.

The story of Kuomintang soldiers and their families retreating to Taiwan after their 1949 defeat is relatively unfamiliar to mainlanders, but there is never a dry eye in the theater wherever it is presented. The humanity in this play is so life affirming one could be forgiven for missing all the wonderful craft that has gone into it.

Like Lai's more famous Peach Blossom Land, The Village is an archetypal theatrical piece that turns the limitations of the stage into an expressive platform. You won't see a film adaptation any time soon, and even if there is one, it's going to lose much of its magic.

I once asked Lai why Chinese cities do not have a theater tradition a la Broadway. His immensely popular plays could have permanent runs in metropolises like Beijing, Shanghai and Taipei, and the same goes for Chinese classics such as Thunderstorm and Teahouse. He said that day would come.

When he first started in Taiwan, in the 1980s, some doubted anyone would show up. Now he is the preeminent Chinese playwright and stage director of this generation and his productions are often sold out throughout Asia.

I am less optimistic that this will happen in the near future, as producing long-running shows and grooming an audience of educated locals and tourists takes time and endlessly rich crops of repertory pieces.

A new theater-going habit is required. Perhaps, the post-80s generation can make that happen.

Li Lei and Han Meimei, starring Jiang Xiaohan (right), tells of the angst and ambitions of young Chinese people. [Photo/ China Daily]

raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

相關(guān)閱讀:

(作者周黎明 中國(guó)日?qǐng)?bào)網(wǎng)英語(yǔ)點(diǎn)津 編輯陳丹妮)